|

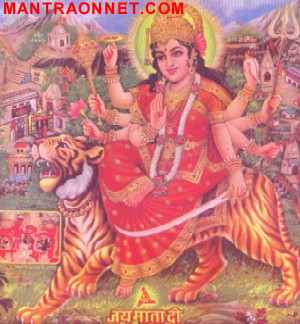

Durga Mata The association of Durga with Rama's success in battle over Ravana in the Ramayana tradition, although not part of Valmiki's Ramayana, has become a well-known part of the Rama story throughout India. In the Kalika-purana we are told: In former times, the great Goddess was waked up by Brahma when it was still night, in order to favour Rama and to obtain the death of Ravana. On the first day of the bright half of the month of Asvina, she gave up her sleep and went to the city of Lanka, where Raghu's son formerly lived. When she came there, the great Goddess caused Rama and Ravana to be engaged in battle, but Ambika herself remained hidden.... Afterwards, when the seventh night had gone by, Mahamaya, in whom the worlds are contained, caused Ravana to be killed by Rama on the ninth day. . . . After the hero Ravana had been killed on the ninth day, the Grandfather of the worlds (Brahma) together with all the gods held a special worship for Durga. Afterwards the Goddess was dismissed with Sahara-festivals, on the tenth day; Indra on his part held a lustration of the army of the gods for the appeasement of the armies of the gods and for the sake of prosperity of the kingdom of the gods. . . . All the gods will worship her and will, on their part, lustrate the army; and in the same way all men should perform worship according to the rules. A king should hold a lustration of the army in order to strengthen his army; a performance must" be made with charming women adorned with celestial ornaments; . . . After one has made a puppet of flour for Skanda and Visakha, one should worship it in order to annihilate one s foes and for the sake of enjoying Durga. In the Devi-bhagavata-purana Rama is despondent at the problems of reaching Lanka, defeating Ravana, and getting back his beloved Sita. The sage Narada, however, advises him to call on Durga for help. Rama asks how she should be worshiped, and Narada instructs him concerning the performance of Durga Pooja or Navaratra. The festival, which Narada assures Rama will result in military success, is said to have been performed in previous ages by Indra for killing Vrtra, by Siva for killing the demons of the three cities, and by Vigr?u for killing Madhu and Kaitabha. Rama duly performs Durga's worship, and she appears to him mounted on her lion. She asks what he wishes, and when he requests victory over Ravana she promises him success, The traditions of Rama's inaugurating Durga Pooja for the purpose of defeating Ravana is also found in the Brhaddharma-purana and the Bengali version of the Ramayana by Krttivasa (fifteenth century) Bengali villagers tell of a tradition in which it was customary to worship Durga during the spring. Rama, however, needed the goddess s help in the autumn when he was about to invade Lanka. So it was that he worshiped her in the month of Asvin and inaugurated autumnal worship, which has become her most popular festival. "When Rama . . . came into conflict with Ravan . . . Rama performed the pooja when he was in trouble, without waiting for the proper time of the annual Pooja. He did the Pooja in the autumn, and later this Pooja became the most popular ritual of the goddess. Durga's association with military prowess and her worship for military success undoubtedly led to her being associated with the military success of both sets of epic heroes sometime in the medieval period. Her association with these great heroes in turn probably tended to further promote her worship by kings for success and prosperity. Durga s association with military might is probably also part of a tradition, most evident in recent centuries, in which goddesses give swords to certain rulers and in which swords are named for goddesses. In the Devi-purana it is said that the goddess may be worshiped in the form of a sword. Shivaji, the seventeenth-century military leader and king from Maharashtra, is said to have received his sword from his family deity, the goddess Bhavani. One account of how Shivaji obtained his sword is phrased as if Shivaji himself were speaking: "I received that famous sword very early in my career as a token of a compact with the Chief Gowalker Sawant. It had been suggested to me on my way to the place where it was being kept that I should take it by force, but remembering that tremendous storms are sometimes raised by unnecessary trifles, I thought it better to leave it to its owner. . . . In the end the wise chief brought the sword to me as a sign of amity even when he knew that its purchase-price was not to be measured in blood. From that day onward the sword, which I reverently named after my tutelary deity. Bhavani, always accompanied me, its resting place when not in use generally being the altar of the goddess, to be received back from her as a visible favour from heaven, always on the Dassera day when starting out on my campaigns." In other legends concerning Shivaji's sword the goddess Bhavani speaks directly to Shivaji, identifies herself with his sword, and is described as entering his sword before battle or before urging Shivaji to undertake the task of murdering his enemy, Afzalkhan.

The Pandyan prince Kumara Kampana (fourteenth century), before going to battle against the Muslims in the Madura area, is said to have been addressed by a goddess who gave him a sword: "A goddess appeared before him and after describing to him the disastrous consequences of the Musselmen invasions of the South and sad plight of the Southern country and its temples exhorted him to extirpate the invaders and restore the country to its ancient glory, presenting him at the same time with a divine sword. " A sacred sword also belonged to the Rajput kingdom of Mewar. The sword was handed down from generation to generation and was placed on the altar of the goddess during Navaratra. According to legend, the founder of the dynasty, Bappa, undertook austerities in the woods. Near the end of his ascetic efforts a goddess riding a lion appeared to him: "From her hand he received the panoply of celestial fabrication, the work of Vishwakarma. . . . The lance, bow, quiver, and arrows; a shield and sword . . . which the goddess girded on him with her own hand." The autumnal worship of Durga, in which she is shown in full military array slaying the demon Mahisa in order to restore order to the cosmos, thus seems to have been part of a widespread cult that centered around obtaining military success. The central festival of this cult took place on Dassera day, immediately following the Navaratra festival, and included the worship of weapons by rulers and soldiers. The worship of a goddess for military success, though not always a part of the Dassera festival, was associated with the festival. Indeed, the two festivals, Navaratra and Dassera, probably were often understood to be one continuous festival in which the worship of Durga and the hope of military success were inseparably linked.

Although the military overtones of Durga Pooja are apparent, other themes are also important during this great festival, and other facets of Durga s character are brought out by the festival. Durga Pooja is celebrated from the first through the ninth days of the bright half of the lunar month of Asvin, which coincides with the autumn harvest in North India, and in certain respects it is clear that Durga Pooja is a harvest festival in which Durga is propitiated as the power of plant fertility. Although Durga Pooja lacks clear agricultural themes as celebrated today in large cities such as Calcutta or as celebrated by those with only tenuous ties to agriculture, there are still enough indications in the festival, even in its citified versions, to discern its importance to the business of agriculture. A central object of worship during the festival, for example, is a bundle of nine different plants, the navapattrika, which is identified with Durga herself." Although the nine plants-in question are not all agricultural plants, paddy and plantain are-included and suggest that Durga is associated with the crops 39 Her association with the other plants probably is meant to generalize her identification with the power underlying all plant life: Durga is not merely the power inherent in the growth of crops but the power inherent in all vegetation. During her worship in this form, the priest anoints Durga with water from auspicious sources, such as the major holy rivers of India. He also anoints her with agricultural products, such as sugarcane juice40 and sesame oil, and offers to her certain soils that are associated with fertility, such as earth dug up by the horns of a wild boar, earth dug up by the horns of a bull, and earth from the doors of prostitutes. It seems clear that one theme of this aspect of the worship of Durga is to promote the fertility of the plants incorporated into the sacred bundle and to promote the fertility of crops in general. At another point in the ceremonies a pot is identified with Durga and worshiped by the priest. Edible fruit and different plants from those making up the navapattrika are placed in the pot. The pot, which has a rounded bottom, is then firmly set up on moist dough. On this dough are scattered five grains: rice, wheat, barley, mas and sesame. As each grain is scattered on the dough, a priest recites the following invocation: "Om you are rice [wheat, barley, etc.], Om you are life, you are the life of the gods, you are our life, you are our internal life, you are long life, you give life, Om the Sun with his rays gives you the milk of life and Varuna nourishes you with water. The pot contains Ganges water in addition to the plants; in a prayer the priest identifies the pot with the source of the nectar of immortality (amrta), which the gods churned from the ocean of milk.

Durga, then, in the form of the pot, is invoked both as the power promoting the growth of the agricultural grains and as the source of the power of life with which the gods achieved immortality. In the forms of the navapattrika and the ghata (pot) Durga~ reveals a dimension of herself that primarily has to do with the fertility of the crops and vegetation and with the power that underlies life in general. In addition to granting freedom from troubles and bestowing wealth on those who perform her Pooja, Durga is also affirmed to grant agricultural produce, and at one point in the festival she is addressed as she who appeases the hunger of the world". Durga's beneficial influence on crops is also suggested at the very beginning of the festival when her image is being set up. The image is placed on a low platform or table about eighteen inches high. The platform is set on damp clay, and the five grains mentioned above are sprinkled in the clay. Although not specifically stated, it appears that the presence of the goddess is believed to promote the growth of these seeds. Furthermore, on the eighth day of the festival the priest worships several groups of deities while circumambulating the image of Durga. Among these are the ksetravalas, deities who preside over cultivated fields. Two other distinctive features of Durga Pooja suggest its importance as a festival affecting the fertility of the crops: the animal sacrifices and the ribald behavior that is specifically mentioned in certain religious texts as pleasing to the goddess. Certainly the sacrifice of an animal, particularly when that animal is a buffalo, suggests the reiteration of the slaying of Mahisa by Durga. But the custom of offering other animals such as goats and sheep and the injunctions to offer several victims during the festival suggest that other meanings are also intended. These blood sacrifices occupy a central role in Durga Pooja. Durga s thirst for blood is established in various texts,50 and this thirst is not limited to the battlefield. Her devotees are said to please her with their own blood, and she is said to receive blood from tribal groups who worship her." Furthermore, other goddesses to whom Durga is closely affiliated, such as Kali, receive blood offerings in their temples daily with no reference at all to heroic deeds in battle. Blood offerings to Durga therefore seem to contain a logic quite apart from the battlefield, or at least quite apart from the myth of the goddess s slaying of Mahisa on behalf of cosmic stability.

It is has been suggested that underlying blood sacrifices to Durga is the perception, perhaps only unconscious, that this great goddess who nourishes the crops and is identified with the power underlying all life needs to be reinvigorated from time to time. Despite her great powers she is capable of being exhausted through continuous birth and the giving of nourishment. To replenish her powers, to reinvigorate her, she is given back life in the form of animal sacrifices. The blood in effect re-supplies her so that she may continue to give life in return. Having harvested the crops, having literally reaped the life-giving benefits of Durga s potency, it is appropriate (perhaps necessary) to return strength and power to her in the form of the blood of sacrificial victims. This logic, and the association of blood sacrifices with harvest, is not at all uncommon in the world s religions. It is a typical ceremonial scenario in many cultures, and it seems likely that at one time it was important in the celebration of Durga Pooja." Promotion of the fertility of the crops by stimulating Durga s powers of fecundity also seems to underlie the practice of publicly making obscene gestures and comments during Durga Pooja. Various scriptures say that Durga is pleased by such behavior at her autumnal festival," and such behavior is suggested in the wild, boisterous activities that accompany the disposal of the image of Durga in a river or pool." The close association, even the interdependence, between human sexuality and the growth of crops is clear in many cultures; 56 it is held to be auspicious and even vital to the growth of crops to have couples copulate in the fields, particularly at planting and harvest time. Again, the logic seems to be that this is a means of giving back vital powers to the spirit underlying the crops. The sexual fluids, like blood, are held to have great fertilizing powers, so to copulate in the fields is to re-nourish the divine beings that promote the growth of the crops. While such outright sexual activity is not part of Durga Pooja, the sexual license enjoined in some scriptures is certainly suggestive of this well-known theme.

Another facet of Durga's character emerges in Durga Pooja but is not stressed in the text? casting her in the role of battle-queen; that is her domestic role as the wife of Siva and mother of several divine children. In North India, which is primarily patrilocal and patriarchal in matters of marriage, it is customary for girls to be married at an early age and to leave their parents home when quite young. This is traumatic for both the girl and her family. In Bengal, at least, daughters customarily return to their home villages during Durga Pooja. The arrival home of the daughters is cause for great happiness and rejoicing, and their departure after the festival is over is the occasion for painful scenes of departure. Durga herself is cast in the role of a returning daughter during her great festival, and many devotional songs are written to welcome her home or to bid her farewell. These songs contain no mention whatsoever of her roles as battle queen or cosmic savior. She is identified with Parvati, who is the wife of Siva and the daughter of Himalaya and his wife Mena. In this role Durga is said to be the mother of Ganesa, Karttikeya, Sarasvati, and Lakshmi. The dominant theme in these songs of welcome and farewell seems to be the difficult life the goddess/daughter has in her husband s home in contrast to the warm, tender treatment she receives from her parents when she visits them. This theme undoubtedly reflects the actual situation of many Bengali girls, for whom life in their husband's village can be difficult in the extreme, particularly in the early years of their marriage when they have no seniority or children to give them respect and I status in the eyes of their in-laws. Siva is described as inattentive to his wife and as unable to take care of himself because of his habit of smoking hemp and his habitual disregard for social convention. The songs contrast the poverty that Durga must endure in her husband s care with the way that she is spoiled by her parents. From the devotee s point of view, then, Durga is seen as a returning daughter who lives a difficult life far away from home. She is welcomed warmly and provided every comfort. The days of the festival are ones of intimacy between the devotee and the goddess, who is understood to have made a long journey to dwell at home with those who worship her. The clay image worshiped during Durga Pooja may show a mighty, many-armed goddess triumphing over a powerful demon, but many devotees cherish her as a tender daughter who has returned home on her annual visit for family succor, sympathy, and the most elaborate hospitality. This theme places the devotee in the position of a family member who spoils Durga with every sort of personal attendance in order to distract her from her normal life with her mad husband, Siva. At the end of Durga Pooja, when the image of the goddess is removed from its place of honor and placed upon a truck or some other conveyance to be carried away for immersion, many women gather about the image to bid it farewell, and it is a common sight to see them actually weeping as the goddess, their daughter, leaves to return to her husband s home far away.

The sacrifice of a buffalo to Durga is practiced in South India too. While agricultural fertility and her cosmic victory on behalf of divine order are themes in this ceremony, Tamil myths and rituals emphasize a quite different aspect of her character. In the Puranas, and in North Indian traditions, there is an implied sexual tension between Durga and Mahisa, her victim. In the South this sexual tension is heightened and becomes one of the central themes of Durga's defeat of Mahisa In fact, most Southern myths about Durga identify Mahisa as her suitor, her would-be husband. Independent in her unmarried state, Durga is portrayed as possessing untamed sexual energy that is dangerous, indeed, deadly, to any male who dares to approach her. Her violent, combative nature needs to be tamed for the welfare of the world. Mahisa is unsuccessful in subduing her and is lured to his doom by her great beauty. A central point of the South Indian myths about Durga and Mahisa is that any sexual association with the goddess is dangerous and that before her sexuality can be rendered safe she must be dominated by, made subservient to, defeated by, or humiliated by a male. In most myths she eventually is tamed by Siva. The South Indian tradition of Durga as a dangerous, indeed, murderous, bride who poses a fatal threat to those who approach her sexually contrasts sharply with the North Indian tradition of Durga Pooja, which stresses Durga's character as a gentle young wife and daughter in need of family tenderness. The South Indian role suggests again the liminal aspect of the goddess. Unlike the weak, submissive, blushing maiden of the Dharma-shastras, Durga presents a picture of determined, fierce independence, which is challenged only at great risk by her suitors. Sourced: www.mantraonnet.com |